It's story which wouldn’t have seemed too out of place on Tales of the Unexpected.

A story of how two FA Cup-winning brothers took a journey from Chile to Barnsley and back again, becoming household names in both England and the South American country of their birth. A story of how, after the siblings finally went their separate ways, one met his end in mysterious circumstances in the Middle East, the heartbreak of the other members of a tight family unit made even more acute by never finding out exactly what had happened.

On Sunday, it will be exactly 50 years since Eduardo ‘Ted’ Robledo, who spent 17 of his 42 years in West Melton, died at sea.

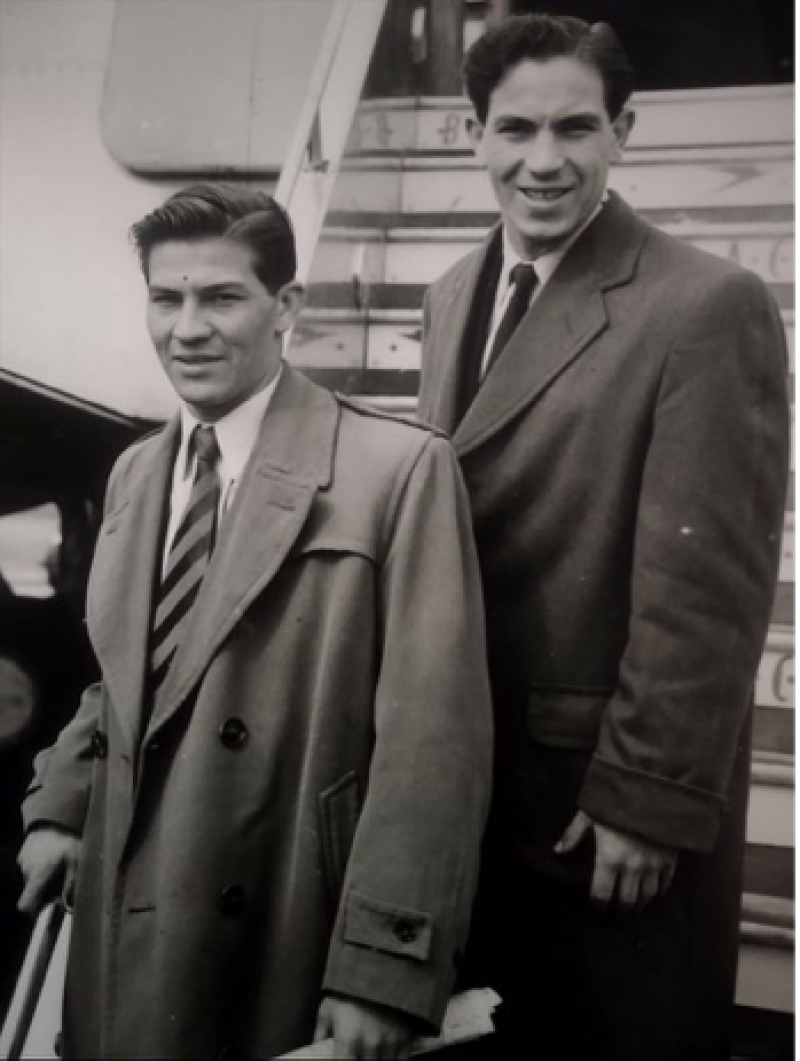

Throughout his football career, it’s fair to say Ted was in the shadow of his elder brother George, alongside whom he played for Barnsley, Newcastle United, leading South American side Colo-Colo and the Chile national team.

While Ted played wing-half, in modern terminology a defensive midfielder, George was an inside-forward, a little like today’s ‘second striker’, whose goal-scoring prowess (47 in 114 games for Barnsley and 91 in 164 for Newcastle) made him a huge hit with supporters.

But for once, it was Ted who made the headlines in December 1970, albeit for tragic reasons.

The remarkable Robledo brothers, the youngest of whom, Walter, decided against pursuing a career in professional football despite showing plenty of promise, were born in the town of Iquique in the north of Chile to Aristides Robledo and Elsie Oliver.

Having left West Melton as a teenager to take up a position as governess to the children of an English mine manager working in South America, Elsie had separated from her Chilean husband when she, George, five, Ted, three, and Walter, six months, returned to the South Yorkshire village in 1932. While their mother set up and ran a general store, all three boys became pupils at Brampton’s George Ellis Senior School, where George, in particular, excelled on the sports fields.

Having played wartime football for both Barnsley and Huddersfield Town, he signed professional forms with the Reds in 1943, when he was 16.

And when the Football League resumed in 1946, he marked his first match by scoring a hat-trick in the 3-2 home Second Division (now Championship) win over Nottingham Forest.

By the time Ted, who like his brother had caught the eye while playing for the Don and Deane representative side, joined Barnsley in 1947, George had established himself in the first team.

Top-flight teams took note of his bright performances, and early in 1949, Newcastle made an offer.

When George said he would only sign if Ted joined too, the Tyneside club agreed to pay £25,000 for the pair, even though the latter had made just five first-team appearances for Barnsley.

It turned out to be a shrewd deal, and George, who represented Chile at the 1950 World Cup in the United States, was a key man as Newcastle beat Blackpool 2-0 to win the FA Cup in 1951.

The following year, he returned to Wembley, this time with Ted in the team, and scored as the trophy was retained with a 1-0 victory over Arsenal.

In 1953, the brothers were on the move again, this time to Colo-Colo, where they twice won the domestic title and regularly represented Chile.

The pair finally pursued their own paths in 1957, and after a brief return to English football with Notts County, Ted, whose marriage to a well-known Chilean dancer was on the rocks, began working on oil rigs, eventually finding his way to the Persian Gulf.

Having gone under the radar for 13 years, Ted was back in the spotlight on December 6, 1970, when he went missing from a ship, the Al Sahn, which had sailed out of Dubai the previous day.

His body was never found.

It was said there had been a fight with the ship’s German captain, Hans Bessenich, who had reportedly invited Ted, who was on shore leave from his rig, to join him on the voyage.

Bessenich was charged with murder, but in a court in Dubai in February 1971, where he claimed Ted had committed suicide, a not guilty verdict was returned.

The judge said there was ‘grave suspicion’ against the captain but that the case could not be proved.