IF four years of war had suddenly come to an end today, the news would travel almost instantaneously.

It would be live on every TV channel, radio station, all over Facebook and every social media network, people’s smart phones would ‘buzz’ with updates and notifications telling them the good news.

But in Barnsley a century ago none of those modes of communication were available.

And so in November 1918 when the First World War came to an abrupt end, the news spread just as quickly, but through much more traditional means.

These included excited word of mouth, and a poster put in the window of the Barnsley Chronicle offices, which were then in Peel Square the building today known as Chambers pub.

It was a Monday, so there was no better way for Chronicle reporters of the day to get the news out.

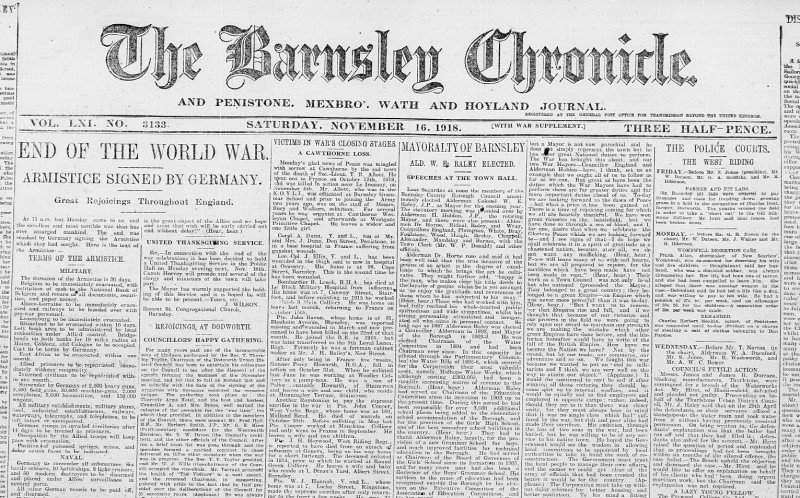

But the newspaper of that week was filled with rejoicing. Here’s how the week’s events were recapped on the front page of the paper on November 16 1918:

“At 11am last Monday came to an end the cruellest and most terrible war that has ever scourged mankind.

“The end was reached by Germany signing the Armistice which they had sought.

“The anxiously-awaited news of the signing of the Armistice was received with great rejoicing throughout the country, the pent-up feelings of the nation finding expression in a unanimous and earnest outburst of enthusiasm.

“During the weekend every scrap of information concerning the progress of the German courier to Spa was eagerly devoured, and on Monday morning, as the fateful hour fixed by Marshal Foch approached, the suspense was intense.

“In Barnsley, as in other towns, the news was awaited anxiously.

“From early morn the people about the streets discussed the situation eagerly, and shortly after eleven o’clock when the joyous tidings came through that Germany had signed the Armistice, these same people gave vent to their pent-up feelings in no uncertain way.

“Market Hill and Peel Square soon became thronged with an enthusiastic concourse of townspeople and when the official declaration was made by a printed poster on the Chronicle windows, all doubts—if any existed—were set at rest.

“It was really astonishing how quickly the glad news spread, and it was equally surprising to find that nearly the whole of the mills and workshops closed as if by pre-arrangement to do so. The workers were too excited to continue their tasks they swarmed into the streets end vigorously shook the hands of their friends.

“Flags, banners, and bannerettes were hoisted from all-manner of buildings, and the children as they dashed from the schools sang with gusto.

“It was a memorable scene, unequalled in the history of man.

“The bells of the Parish Church rang a merry peal and the entire town was given up to holiday. To the credit of the townspeople there was no sign of rowdyism, and Monday’s rejoicings were in direct contrast to the never-to-be-forgotten demonstrations when the settlement of the Boer War was reached.”

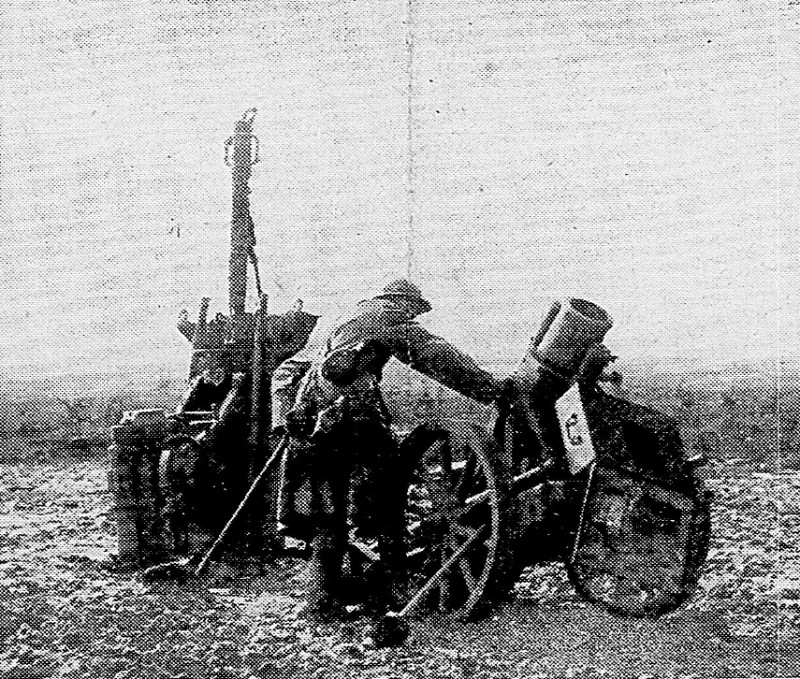

A century on it is hard to imagine the level of joy and excitement in the streets. But it would of course be bittersweet for the friends and relatives of some 4,000 Barnsley men who would not be returning home.

And as fighting continued up until the 11th hour, and given communication was slow, there would still have been bad news in store for many after the signing of the Armistice.