Jamie VARDY to Huddersfield, Peter Beardsley to Leeds, Diego Maradona to Sheffield United.

Like fishing, football is full of tales of the one that got away, when clubs missed chances to do deals for then-unknown players who turned out to be diamonds.

There’s a pretty compelling case for claiming Barnsley’s biggest blunder came back in the late 1920s, when they gave a trial to a local lad named Wilf Copping – and turned him down.

Teenager Wilf, who played for teams such as Dearne Valley Old Boys and Middlecliffe Rovers while working down the pit, went on to play for Leeds and Arsenal, with whom he won two titles and the FA Cup, and earn 20 England caps in an era when far fewer internationals were played.

And in 1998, he was named alongside household names like Billy Wright, Bobby Charlton and Alan Shearer as one of the centenary-celebrating Football League’s 100 legends.

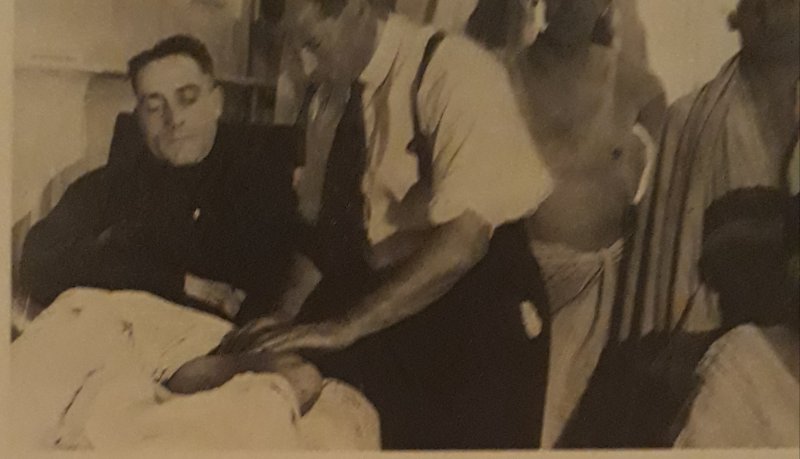

With his craggy appearance, five o’clock shadow (not shaving on matchdays was among his many superstitions), bone-shaking shoulder charges and crunching challenges, Wilf both looked and played the part of one of football’s hard men.

A midfield ‘enforcer’, his mantra was ‘the first man in a tackle never gets hurt’, but there was far more to his game than brute force and he was considered a fair, if formidable, opponent.

A quick thinker and deft passer of the ball, he could turn defence into attack in the blink of an eye, and he also had a useful long throw in his repertoire.

A little like Roy Keane, Wilf had a steely determination and intensity about him, and fellow Arsenal and England player Ted Drake later recalled: “I soon learned not to push him too far.

“Before his Arsenal debut, I was busy chatting to him the dressing room, but he kept ignoring me. So, I tapped him on the shoulder. Big mistake!

“He grabbed me by the collar and shouted ‘I want quiet. Is that clear? You could say I got the message.”

Even when representing what many termed the ‘Bank of England club’, he remained grounded. Drake added: “I think Wilf tended to look on football the same way Richard Burton, the son of a Welsh miner, viewed acting.

“Wilf often said he couldn’t believe how cushy a life footballers had, especially those in London. He almost seemed embarrassed sometimes.”

Perhaps that was down to his no-nonsense Barnsley upbringing.

Born into a big family in Middlecliffe on August 17, 1909, he attended Houghton Council School before starting work as a miner while playing local-league football.

Undeterred by rejection by the Reds, Wilf sought a trial at Leeds, and was this time successful, signing for the Elland Road club in March 1929, when he was 19.

He had to bide his time, but when an injury to regular left-half George Reed provided an opening, he took it, and became a regular in the 1930/31 top-flight campaign. Leeds were relegated, but with Wilf, Willis Edwards and Ernie Hart forming an impressive half-back line, promotion from the Second Division was won at the first attempt, and Leeds finished eighth in Division One in 1932/33 and ninth in 1933/34.

Arsenal won the championship in both those seasons, and when George Allison, who became manager following the death of the legendary Herbert Chapman in January 1934, decided it was time to replace the veteran Bob John, he turned to Wilf, by now an England regular.

An £8,000 transfer was agreed in June 1934, and the Gunners went on to win a third successive title.

In November 1934, Wilf was one of seven Arsenal players selected by England to face recent World Cup winners Italy at Highbury, and in a bruising encounter, had one of his finest matches in a 3-2 victory.

Having helped Arsenal win the FA Cup in 1935/36, when Sheffield United were beaten 1-0 at Wembley, a second title medal was earned in 1937/38, before he rejoined Leeds in March 1939.

Wilf, who also played twice for the Football League representative team, served in North Africa during the Second World War. After the hostilities ended, he had a spell coaching in Belgium before returning to England to work for Southend, Bristol City and Coventry.

In 1959, he retired and went to live in Southend, where he died in June 1980, aged 70.